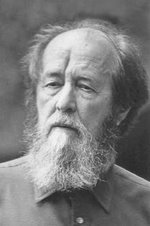

It’s been years since I have read Gulag Archipelago, years in which the Soviet state has fallen, Russia becomes a real word, not an imprecise synonym of “Soviet”, years in which I felt the essential Solzhenitsyn was in First Circle and Cancer Ward, and Cancer Ward began to have prmacy over First Circle as the greatest novel, for it was the most universal.

So because Thomas lists Gulag as one of Aleksandr Isayevich’s best books, and because I have a paperback copy in the local library, I take it up. It is one of the first English paperback editions, the cover design I well remember, grey with blue letters, the slightly delineated figures standing in a group behind barbed wire (essentially heads ahd shoulders, only a few lines for legs). But the first startling thing, this book I remember so well, somehow in the years since 1974 has acquired quite small print. I can read it, even the footnote, but why did I never notice before how small the letters were?

The narrative grabs as before, although with a difference. The details, the names I don’t know (Levitan, Krylenko, Tambov province, etc. etc.), pour across the pages as before. But in the 70’s I read these names and tried to remember them, for this was important, this was how the Soviet Union began, now I read them and think of ancient history. There was a Soviet Union once, my daughter will be able to say she and it were briefly alive together, it ended three weeks before her second birthday. But Solzhenitsyn’s writing is still as good, the same humanity and delightful ironies flow with the unknown names.

And then I am in the Bluecaps chapter, and the great words “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his heart?” And the next morning I read about the bit of God’s heaven condemned to float above the Lubyanka, and when I put the book down to start the morning commute, I walk outside, and above the sky attracts my eye, the pink glowing cloud glows brighter to my mind because Aleksandr Isayevich has written about how precious sky can be to a prisoner.

Why is the story still great, even though it is no longer immediately relevant? Why is it still precious to me, even though the reality that the USSR as an evil empire is no longer a new idea? One thing, Solzhenitsyn writes in my internal language, the idea that all around are details which can become precious as we examine them. A small patch of sky, a small bowl of food is precious. Another enjoyable thing is Solzhenitsyn’s use of irony. “those present immediately broke open the ice encasing the specimens and devoured them with relish on the spot.” (first paragraph of preface).

Friday, February 9, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment